A pioneering collaboration between our Ophthalmology team and the University of Cambridge has the potential to eradicate an eye disease that affects some Old English Sheepdogs.

The discovery by veterinary clinicians and geneticists has identified the genetic variant that causes an inherited eye disease syndrome in this breed. This has enabled the development of a DNA test that dog breeders can use to prevent breeding dogs with this problem in the future.

The breakthrough is through our Specialist vets with research associate Katherine Stanbury and senior research associate Cathryn Mellersh, both from the Kennel Club Genetics Centre based in the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Cambridge.

It has also been made possible by a grant from the Dogs Trust and support from the Kennel Club Charitable Trust.

The research started when James Oliver, our Head of Ophthalmology who conducts inherited eye disease testing at DWR, examined an Old English Sheepdog used for breeding and found it to have cataracts.

The dog who was referred by their local vet for a more detailed examination and diagnosed with cataracts and multi ocular defects, so it wasn’t suitable for breeding but still needed medical care.

James said: “The dog had multiple eye defects. We do see this occasionally in various breeds, including Old English Sheepdogs. Not a lot is known about it and we didn’t know how it is inherited or what potentially the genetic base of the disease might be.

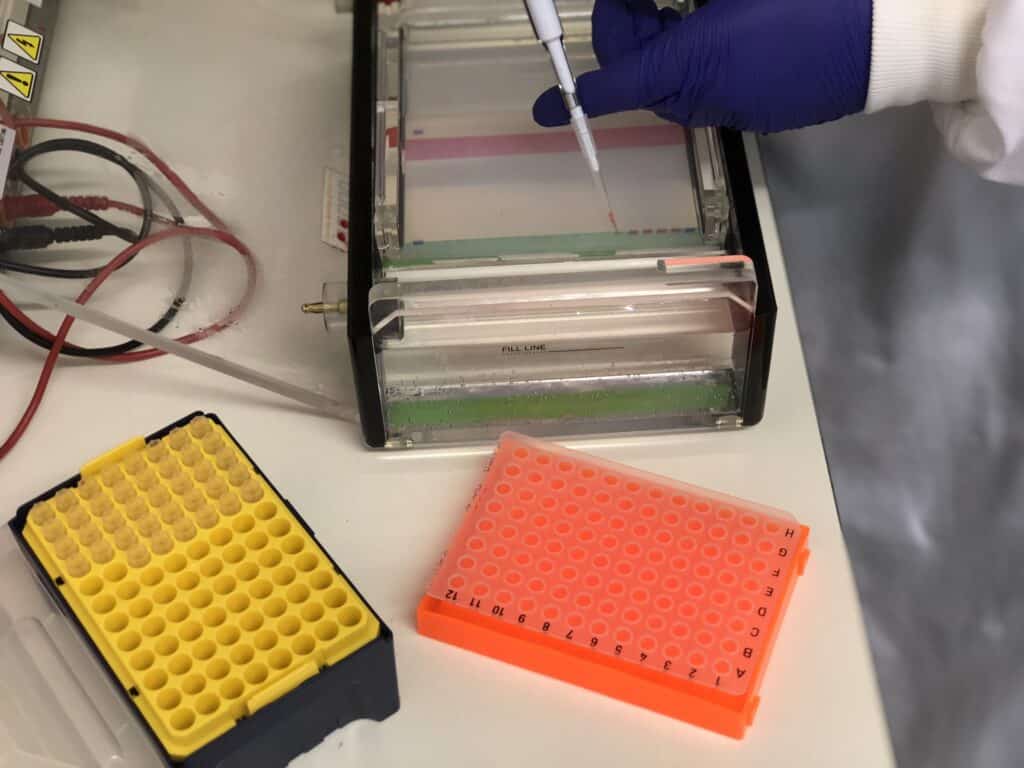

“This kickstarted the project and, as vets, we collected DNA samples from several dogs with similar problems and the geneticists discovered the gene involved, and the specific mutation within that gene which seems to be causing the blinding eye problem within this breed.

“The Old English Sheepdog is quite a rare breed and it only takes a very small number of breeding animals who carry a genetic defect for that mutation to become more widespread.

“Now we’ve discovered the gene causing the issue, we’ve established a DNA test so that Old English Sheepdog breeders can use this test to work out if their dogs carry the mutation and, therefore, make sensible breeding decisions to ensure affected puppies are not produced going forward by inappropriate mating.”

Cathryn added: “Projects such as these need four parts to complete the puzzle. It requires the clinicians, the geneticists, owner cooperation and funding.

“Working with DWR has been vital to the success of this research. When you know the underlying defect you can develop a DNA test so that breeders can use it to prevent the disease happening in the future.

“It is very exciting that we have found the genetic cause and breeders can test their dogs for the mutation.

“It’s also a great example of clinicians and researchers working together to benefit animal welfare.”

At present, the only DNA testing service to offer the test, priced at £48, is Canine Genetic Testing (https://www.cagt.co.uk/) which is based at the University of Cambridge and operates alongside the canine genetics research team.

Katherine said: “Breeders need to test both parents as we believe the gene to be dominant, meaning dogs only need to inherit a single copy of the mutation to be affected.

“We also believe that dogs with two copies might have more wrong with their eyes. The test will allow breeders to only breed dogs who are clear of this mutation. Prevention is better than cure.”